One aim of organic farming under European legislation is to “combine best environmental practices, a high level of biodiversity, [and] the preservation of natural resources". Moreover, a recent study showed that organic farming beats conventional farming in social benefits, profitability, and offers more ecosystem services. Sounds good, right?!

If it sounds so good, why haven’t all farmers converted to organic farming by now? In Germany, only 6.2% of the farmland is under organic management, far short of the national goal of 20% (Federal Statistical Office, 2014, p. 42). What motivates farmers to produce organic products, and which barriers do they face?

In my Master’s thesis at Uppsala University, supervised by Kim Nicholas at Lund University as part of the OPERAs Wine Exemplar, I explored exactly these motives and barriers to convert to organic farming. The organic wine sector doubled in Germany between 2007 and 2012, while other agricultural sectors saw slow conversion rates. I wanted to know, what motivates and what hinders wine farmers to convert to organic management?

Figure 1: Out in the vineyards of Pfalz and Rheinhessen.

To investigate these motives and barriers, I interviewed four organic and four conventional wine farmers in the two largest German wine regions, Pfalz and Rheinhessen (see my blog post about first impressions after the interviews). I asked about their views in five capitals: natural (environmental resources), human (personal values), social (societal influences), financial (financial resources) and physical (supporting objects such as infrastructure and technology).

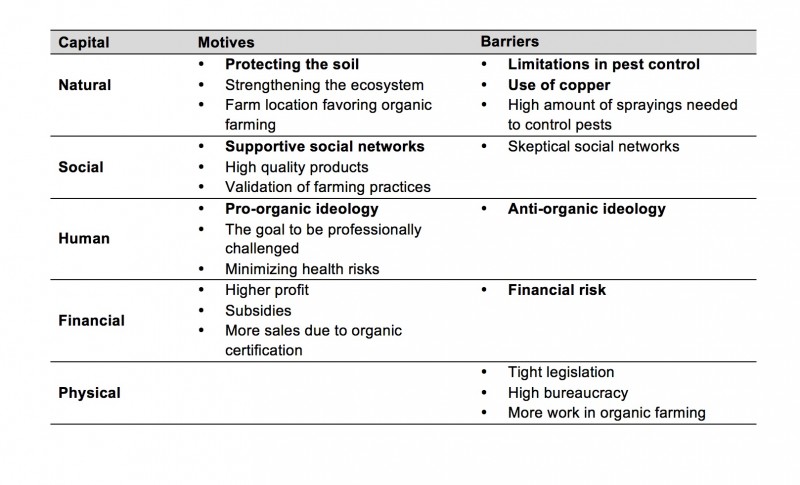

As a result of the interviews, I found 12 motives and 9 barriers to convert to organic farming (Table 1).

Table 1. Motives and barriers in the perception of eight interviewed wine farmers (four organic, four conventional) to convert to organic farming in Pfalz and Rheinhessen. Topics which were mentioned by at least two farmers are illustrated split up in the five different capitals: natural, social, human, financial and physical. The most important topics are shown in bold.

The most important motivations of wine farmers were the protection of the soil, supportive social networks, and a pro-organic ideology. First, the organic wine farmers I interviewed were motivated to convert to organic farming to protect the soil. For instance, they saw it as a high value to forgo synthetic pesticides in their vineyards. One organic farmer told me: “Only with healthy soils can we produce good grapes and from these make good wine”. However, conventional farmers also had this goal, as one conventional farmer described that environmentally friendly farming “is absolute common sense meaning an orientation towards a better ecologic balance in the soil”.

Second, supportive social networks had a huge impact on farmers’ perceptions of organic farming. For instance, one organic farmer told me how important good examples in the direct social environment of the farmer are: “We were the first organic business in this village. We followed suit after other [estates] where we saw that they achieve good results with organic [farming] and now we are already six or seven estates in this village.”

Third, a positive ideology towards organic farming was an extremely important motivation for farmers to convert to organic farming. An organic farmer was convinced that all farming should be done organically certified: “If you ask me, there shouldn’t be anything else [than organic farming]. (…) I think that we are all responsible to nurse our environment.”

Furthermore, all the interviewed farmers sold at least one wine at one of the world’s biggest wine retailers, the Swedish government-owned alcohol monopoly Systembolaget. In the perception of the farmers, Systembolaget plays a supporting role in the adoption of organic farming by providing demand for environmentally friendly wines, but it was not the main driving factor in the conversion process. An organic farmer told me: “It is apparently so that it [organic certification] facilitates our survival (…). So the world is shipshape for me”.

In contrast, I found four main barriers preventing conventional farmers from adopting organic viticulture: an ideology which is against organic farming principles, limitations in pest control, the use of copper, and financial risk in the adoption of organic farming practices.

First, an ideology which is not in line with the European organic legislation created an important barrier in converting to organic farming. For instance, one farmer was most concerned about the emissions of greenhouse gases causing climate change, which the European organic legislation does not take into account: “The main killer of the environment is rather CO2 and less these measures [synthetic pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers]”.

Moreover, wine farmers were concerned about the pest control measures allowed in organic farming. Synthetic products are forbidden by organic regulations, so a farmer has fewer options to treat pests, a limitation of concern to some farmers. One organic farmer explained that the risk of fungi is the same for organic and conventional vineyards, only the “possibilities to react make the difference,” which other organic farmers saw as the main challenge.

Thirdly, organic regulations permit some measures that conventional farmers found questionable. Copper, for instance, is used to treat the fungal disease downy mildew in organic viticulture, but can accumulate in the soil as a heavy metal, potentially polluting the soil.

Finally, some farmers saw the financial risk to convert to organic farming as too high, because production costs would increase, but neither subsidies nor premium prices could cover the higher costs. The need to make a profit was exemplified by one farmer in talking about the risk of not breaking even: “And then are we already at the end of the line of argument”.

To sum up, this research indicates that if Germany wants to reach their goal of 20% organic farmland, they could benefit from policies that would support the motivations for organic agriculture, and help remove some of the barriers. Specifically, since the farmers’ ideology and the attitude of their social networks were extremely important, education campaigns on the benefits of organic farming could be considered. Moreover, products to fight pests in organic farming, such as copper, should be evaluated for its overall environmental impacts, and alternatives considered. Finally, to lower the financial risk, insurance strategies, diversification, or increased subsidies for organic farming could be options. Finally, as working together with Systembolaget supported organic farming, Germany could engage in further collaborations with retailers.

My thesis shows that organic farming plays a crucial role in delivering ecosystem services. Thus, certifications including the European label for organic farming can be seen as one potential way for sustainable development, and should be acknowledged as a way to increase transparency and give power to the consumer. Wine farmers in Germany are motivated and open to discuss different farming practices. Thus, there is great potential to increase organic farmland if the political will from the national organic goal is translated in further actions.